Writing with images

In visual ethnographic work, the challenge of finding form is not just a technical concern - it goes to the heart of the research itself. This blogpost explores this challenge by discussing some of the choices behind the visual storytelling of this research project.

The value of visual ethnographic work

We know that visual research methods open up collaborative ways of working, different kinds of knowledge, and fresh approaches to critical theory. When these methods result in visual outputs - like film, photography, or other artistic projects - they are often hoped to be more accessible than the dense theoretical texts locked behind academic paywalls. Some even say we are at the start of a new era for academic research, where art is not just added to the ethnographic practice but changes the very way it is thought.

Visual anthropology may be all that (and more), but it is also ‘simply’ a response to the central research question: how to do good research. Don’t we seek the right methods to reach meaningful results? Aren’t we closely examining the concepts we use, the theories we engage, and the people or cases we select? To me, using visual methods and outputs is simply an extension of that critical thinking. Why would we be so careful with the words we choose, yet so rarely question that it’s words we’re choosing? Thinking with the senses means acknowledging that there is no single, best or default form for communicating research. Every project becomes a new challenge of finding the right form.

Challenge 1: Privacy in visual ethnography

There are many ways to hide a person’s identity in film: distorting their voice, blur their faces, focus on their hands. We did not actually want to hide a person, we wanted to reveal them: their personality, their stories, lives and the way they made sense of it all. So how could we do that without revealing their identity?

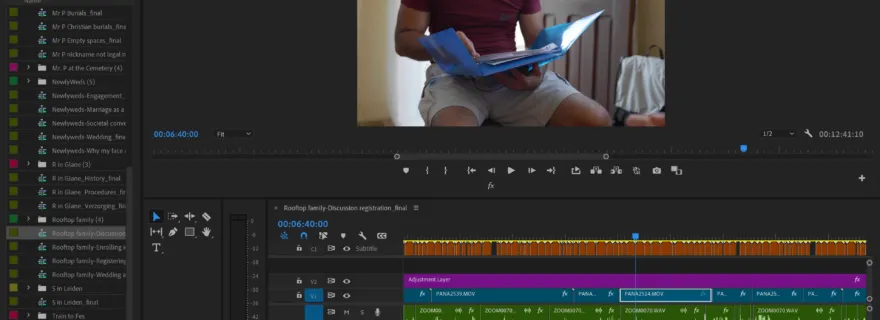

When editing this video, I played with using the blue transparent document folder as a visual metaphor for the story that the couple is telling. As we dive deeper into a story of confusing bureaucracy, we also become increasingly lost in this folder.

Challenge 2: Language limitations when filming

Film editing, much like writing, is deceitful. Depending on how it is cut and stitched back together a completely different story can emerge. The previous video was edited into a coherent narrative, even though the interview itself was long and confusing.

The challenge here was that I didn’t speak Urdu, meaning I was filming an interview without understanding what was being said. To complicate matters, the translator wasn’t a native Urdu speaker, the couple didn’t fully understand the legal procedures they were subjected to, and the interview stretched on for many hours which tested everyone’s concentration.

As a result, the interview was full of glitches - pauses, diversions, confusions, and missed connections. In the first video, I edited those out. But in this second video about the process, I tried to reveal them. I worked with the same material but chose a form that visually communicated the lived experience of that conversation.

Read more about Ahmed and Fatima's story and the registration of their son's birth, or read about how Judith, the researcher, reflects on the interview.